Working with Faceted Geometry in Ansys Fluent Meshing

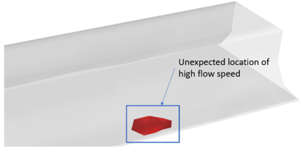

Faceted geometry comes in several different formats with OBJ, PLY, and STL being commonly used. Some simulation tools require solid geometry before importing. Fortunately, Fluent Meshing is designed to work with surface models. These faceted file formats are often the standard when working with 3D scanned geometry in the medical community and in the field of additive manufacturing. Faceted geometry approximates a geometric shape by representing it as a triangular surface mesh rather than using a solid body representation. Many commercial CAD and CAE packages do not natively represent geometry using facets but use a technique called Constructive Solid Geometry (CSG) to represent geometry which is the process of combining simple shapes using Boolean operations to create more complex shapes. One of the issues when working with faceted geometry is CSG-based CAD and CAE programs are not well equipped to convert the surface mesh associated with faceted geometry into a solid, and it can be a time-consuming process to do so.

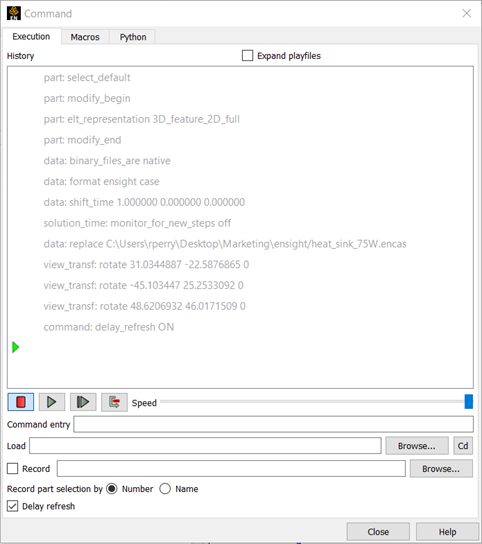

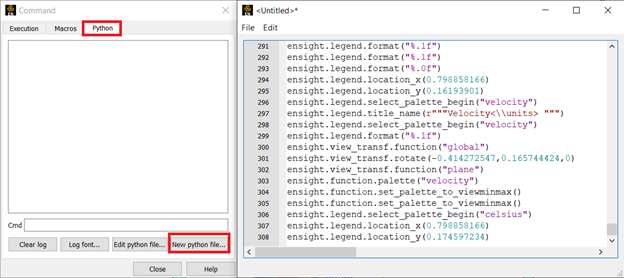

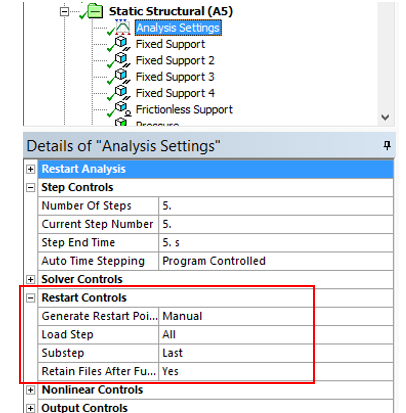

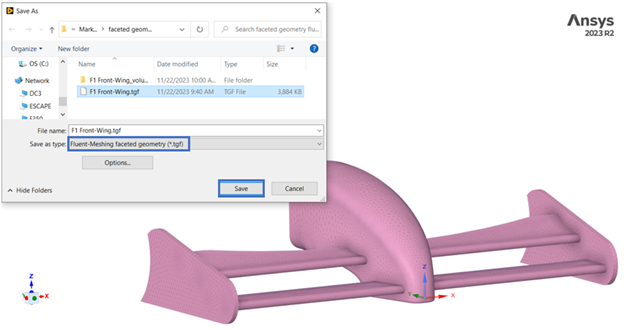

Fluent Meshing (a feature in Ansys CFD licenses) can work directly with faceted or solid geometry. The user will need to use Ansys Discovery to convert the faceted geometry file (OBJ, PLY, STL, etc.) into a TFG (Fluent-Meshing faceted geometry) before reading into Fluent Meshing. See below:

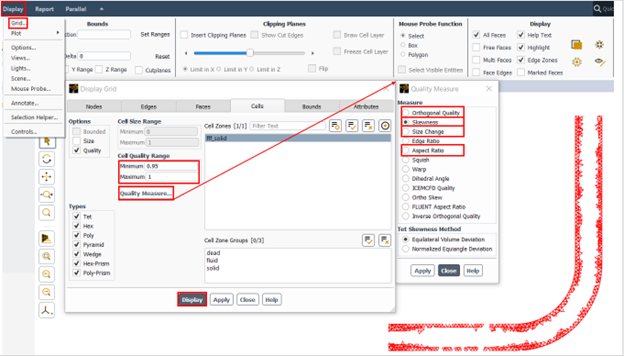

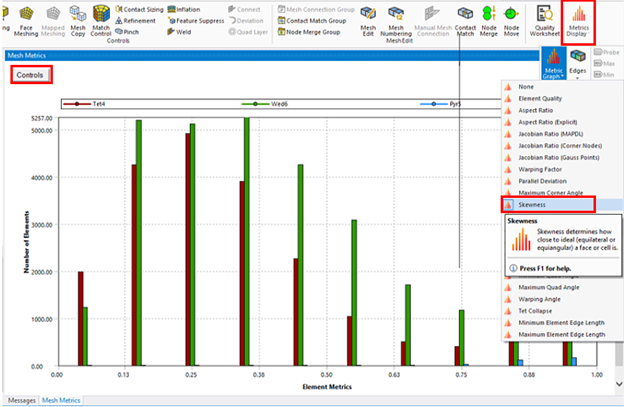

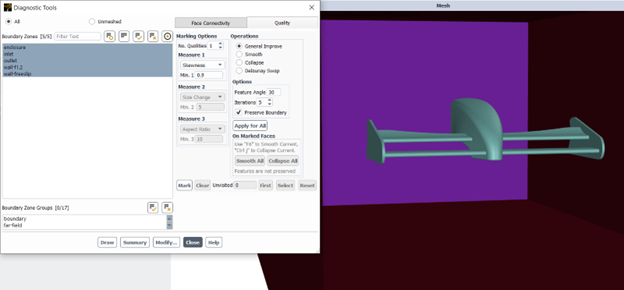

All the named selections and geometry preparation that was done on the faceted geometry in Ansys Discovery will be preserved in Fluent Meshing when reading in the TGF. The user can then use some of the mesh diagnostic tools in the Outline View to evaluate the quality and check for connectivity issues if needed. There are automatic operations that can be used to improve the quality of the mesh as required. See below:

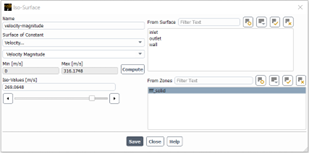

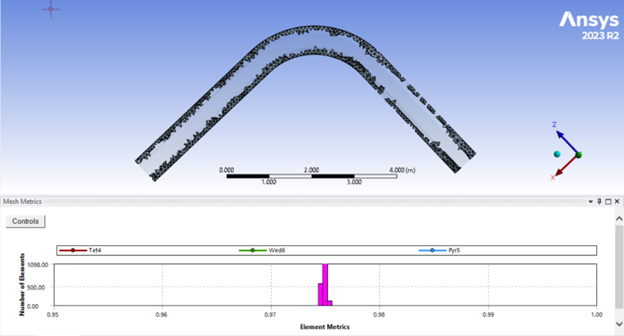

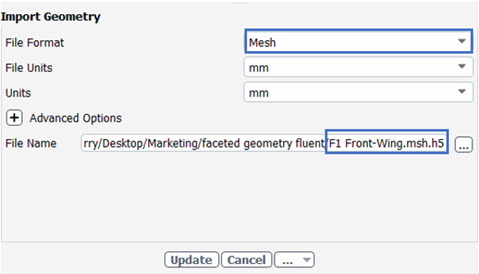

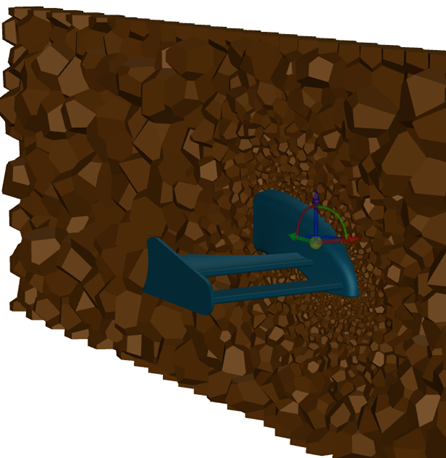

The user can generate the volume mesh in the Outline View or use one of the more user-friendly task-based workflows such as Fluent Watertight Workflow. The task-based workflows do not yet support TGF geometry import, so the user will need to write out a .msh.h5 in Fluent Meshing before reading into the workflow. See below:

It is business as usual with the faceted geometry loaded into the import geometry task of the workflow. The user will start from the top and work their way down in the task-based workflow until a volume mesh is generated.

Some engineering tools require that geometry be represented as a solid, and it can be challenging to convert faceted geometry into a solid in many cases. Fluent Meshing is designed to work with surface models so faceted geometry does not need to be converted into solid before import. This can be a quality-of-life improvement when working with surface representations of solid bodies in Ansys CFD products.